By Gaetano Cipolla

Hello everyone, my name is Gaetano Cipolla, Professor Emeritus St. John’s University and President.

Today I want to share with you a sample of an important project that I have been working on. And which would take a long time to bring to fruition. I will share with you a sample of what I have been doing.

You may know that the Sicilian School of poetry that flourished in the early part of the 13th century at the court of Emperor Frederick II represents the beginning of Italian literature, that is literature written in an Italian language that was not Latin. The poets of the Scuola Siciliana who were courtiers, bureaucrats, notaries at the court of Frederick wrote in Sicilian and established the literary canon. The language they used became the standard for poetry in all of Italy and was used even by poets who were not Sicilian. In fact, Dante Alighieri acknowledged the importance of the new language by saying that for the first 150 years of Italian literature what poetry was written was written in Sicilian. Sicilian was the first language emerging from Latin to be used for poetry. As I like to say, if Dante was the father of the Italian language, we probably should credit Sicilian as the mother.

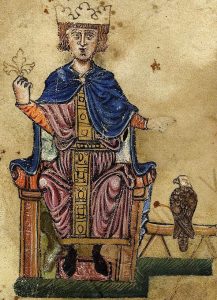

Frederick II, the Stupor Mundi

When Frederick II died in 1250 and when the Ghibelline forces were defeated in 1266 in the battle of Benevento, his importance in Italian matters came to an end. As a result of the diminished role of the Ghibellines in the political, cultural, and social life on the Italian peninsula, the cultural artifacts that had been produced by the Emperor and his associates faded, either by design of the victors or by neglect. I cannot say whether there was a conscious attempt to eradicate the legacy of Frederick II, as happens usually when the opposition comes to power. But the fact remains that practically all the original poetry produced in the Sicilian School, with few exceptions, disappeared. What remained are copies as transcribed by Tuscan amanuensis who transcribed them not as they were written but in Tuscan. The scribes changed the rhyme words, words were spelled according to their own language and basically altered the original Sicilian so that it is almost unrecognizable as Sicilian.

My intention is to rewrite the poetry of the Sicilian School to recapture the sounds, the musicality, and the rhythm of the originals. Naturally, the Sicilian of today has evolved and it is different from what it may have been in the 13th century. Nevertheless, I think that by substituting Sicilian endings, changing words to what may have been the original will go a long way to restoring the original sounds. So far, I have rewritten two sonnets and a canzone by Giacomo da Lentini who was the acknowledged leader of the group. I have also translated them into English. I will recite the Sicilian version first and then my English translation. Giacomo da Lentini was the poet who invented the sonnet by adding six lines to the eight-line poem that is the traditional composition used by Sicilian poets, like Antonio Veneziano and Giovanni Meli. The first sonnet is well known, in fact, the conclusion of it was used in the first aria of Cavalleria rusticana when Turiddu sings to Lola that if he dies because of their transgression and goes to paradise, if she is not there, he would refuse to enter paradise.

Eu m’aggiu postu in cori a Diu sirviri,

com’eu putissi jiri in paradisu,

ô santu locu, c’aggiu auditu diri,

o’ si mantien sollazzu, giocu e risu.

Sanza mia donna non vi vurrìa jiri,

chidda c’à biunda testa e claru visu,

ca sanza lei non putirìa gaudiri,

estandu da la mia donna divisu.

Ma no lu dicu a tali intendimentu,

perch’eu piccatu ci vulissi fari;

si non vidiri u so bel portamentu

e lu bel visu e ’l morbidu sguardari:

chi ‘l mi tirrìa in gran consolamentu,

vidennu la mia donna in ghiora stari.

I have decided to serve God, our Lord,

So I may earn a place in Paradise,

that holy realm that I have often heard

merriment, laughter and great joy supplies.

Without my lady though, I would not go,

the one who has blond hair and a bright face,

because without her I just would not know

what joy is were she in another place.

But I do not say this because I mean

to perpetrate a sinful act with her;

I simply want to see her noble mien

and her sweet face and her soft loving eyes.

Oh what great consolation, oh how keen

to see my lady basking in her praise!

it would be a most welcome consolation

to watch my lady in her glory station.

This is the second sonnet that describes the power of love

Sonnet 26

A l’airu claru ò vista ploggia dari

Ed a lu scuru rendiri claruri;

e focu arzenti ghiaccia divintari,

e fridda nivi rendiri caluri

e dulzi cosi moltu amariari,

e di l’amari rendiri dulzuri;

e dui guerreri nfini a paci stari,

e ‘nfra dui amici nascirici erruri.

Ed ò vista d’Amor cosa chiù forti,

ch’era firutu e sanòmi firendu,

lu focu dunni ardia stutò cun focu;

la vita chi mi dè fue la mia morti,

lu focu chi mi stinsi ora ne ‘ncendu,

d’amor mi trassi e misimi in su’ locu

and here is the translation

I have seen rain fall when the sky was clear

And darkness being rent by glowing light

And burning blazes turn to frozen ice

And ice-cold snow start radiating heat;

And sweet things mightily becoming sour

And bitter things become sweet to the taste

And two harsh warriors abide in peace

And in good friends some enmity arise.

And even stranger things I’ve seen of love

Who wounded me and healed me wounding me;

dousing with fire the flame ablaze in me

The life it gave me was in truth my death

The fire he put out now burns within me

He took love out and put me in his place.

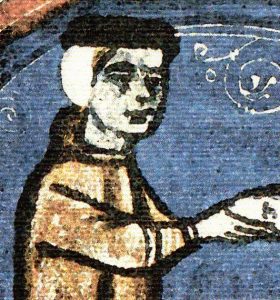

Jacopo da Lentini

The canzuna that follows is a beautiful composition that describes the effects that a woman has on the poet:

Miravigghiusamenti

Miravigghiusamenti

n’amuri mi distrinci

e mi teni ad ogn’ura.

Com’omu ca poni menti

in àutru exemplu pinci

la simili pintura,

cussì, bedda, facc’eu,

ca ’nfra lu cori meu

portu la to figura.

In cori pari ch’eu vi porti,

pinta comu pariti,

e non pari difora.

O Deu, comu mi pari forti

non so si lu sapiti,

com’ v’amu di bon cori;

ch’eu sù sì virgugnusu

ca pur vi guardu ascusu

e non vi mustru amuri.

Avennu gran disiu

dipinsi una pintura,

bedda, vui sumigghianti,

e quannu vui non viju

guardu nni dda figura,

pari ch’e v’aggia avanti:

comu chiddu chi cridi

salvarsi pir sua fidi,

ancor non veggia inanti.

Al cor m’ard’una dogghia,

com’om chi teni lu focu

a lo so senu ascusu,

e quannu chiù lu ’nvogghia,

allura ardi chiù ddocu

e non pò star inclusu:

similementi eu ardu

quannu pass’e non guardu

a vui, vis’amurusu.

S’eu guardu, quannu passu,

inver’ vui no mi giru,

bedda, pir risguardari;

andannu, ad ogni passu

jettu un gran suspiru

ca facimi ancusciari;

e certu beni ancusciu,

c’a pena mi conusciu,

tantu bedda mi pari.

Assai v’aggiu laudatu,

madonna, in tutti parti,

di biddizzi c’aviti.

Non so si v’è cuntatu

ch’eu lu faccia pir arti,

che vui pur v’ascunditi:

sacciatilu pir singa

zocch’eu no dicu a linga,

quannu vui mi viditi.

Canzunedda nuvella,

va’ canta nova cosa;

lèvati di maitinu

davanti a la chiù bedda,

ciuri d’ogn’amurusa,

biunda chiù c’auru finu:

«Lu vostru amuri, ch’è caru,

dunatilu a lu Nutaru

ch’è natu di Lentinu».

Extraordinarily

Extraordinarily

A love constrains me so

I’m so constrained by love

it never lets me go.

Like one who puts his mind

to paint a likeness of

a model he can view,

that’s all I do, my love,

I carry in my heart

an effigy of you.

I bear you in my heart

painted as you appear

but this outside won’t show.

God, it is harsh, severe,

not knowing if you know

that my love is sincere.

However, I’m so shy

I watch you on the sly

and hide the love I bear.

Moved by a strong desire

I drew a lovely portrait

that close resembled you

and when you’re not in view

that image I admire

and think I’m seeing you.

Like someone who believes

his faith can save his soul

though he can’t see that goal.

There’s burning in my heart

like one who has a fire

that’s hidden in his breast,

and when incitement soars

the flame grows even higher

so he can’t take much more.

That is the way I burn

when I pass by and turn

away from you, my love.

If when I pass, you’re there,

I do not turn to stare,

my love, to better see,

but with each step I try

I breathe a heavy sigh

that takes my breath away.

I feel then so unsteady,

who I am I can’t say,

so fair you seem, my Lady.

Much praise did I accord,

Lady, to you for all

the beauties you possess.

I know not if you’ve heard

it’s done with craftiness

that’s why you hide from view,

but take this as a clue

of what I’ll say to you

when you and I will meet.

My little novel song,

go sing of something new.

Rise early in the morn

and seek the fairest one

among the best in love,

whose hair is fine spun gold.

“Your love that is so rare

give to the Notary

who’s from Lentini born.”

Frederick II wanted to create a lay culture to offer an alternative to the Latin-based culture that was primarily in the hands of the Church. He founded the University of Naples in 1224 to create a class of bureaucrats who could run his empire efficiently. The Sicilian School was a political statement as well as a literary endeavor. The poets continued the tradition established by the Provençal poets. In continuing that tradition, they made a great contribution not only by inventing a new language but also by devoting their attention to one exclusive theme. While the Provençal poets wrote about all kinds of subjects, war, politics, and many social issues, the Sicilians devoted their poetry to the theme of love, a practice that was continued by the poets who followed them, such as the poets of the Dolce Stil Novo, Dante, Cavalcanti, Petrarch, Boccaccio and the others.

Tomb of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor Cathedral of Palermo

They pioneered the cult of love and they explored every aspect of it. This is ironic when you think that the 13th century was constantly at war, struggling with famine and pestilence, but the Sicilian poets wrote only about love! There was another reason for this, however. Frederick II passed a law that no one was allowed to write about him in a disparaging way.

Thanks for watching.